Academics

"If you can't show us how to kill the grasshoppers, you can do nothing for us."

Skeptical farmers, to the newly hired agricultural agent

Research

"Lacto" Intolerant

In 1913, the college dairy department announced it had manufactured a new food product, "lacto," which closely resembled ice cream. Lacto was made from skim milk treated with a commercial pure lactic acid, making it both cheaper and healthier than ordinary ice cream.

Although the hope that there would be a market for such a product went unfulfilled, making better ice cream continued to be serious business in the dairy department. An article in a 1935 issue of The New Hampshire boasted that the dairy produced about 12,000 gallons of ice cream annually (9,000 of which were consumed on campus). There were 30 different flavors, including ginger, fruit salad, and mint pineapple, plus several kinds of sherbets and a chocolate ice cream sandwich.

Grasshopper Stopper

The 1914 Smith-Lever Act provided funds for cooperative extension work in agriculture and home economics between the land-grant colleges and the US Department of Agriculture. These funds made it possible to organize demonstration work on a county-wide basis.

Arthur Davis, Class of 1912, was hired to serve as the agricultural agent for Merrimack County. The farmers, many of whom were skeptical of the program, told Davis, "If you can't show us how to kill the grasshoppers, you can do nothing for us."

Davis turned to his alma mater for help. The solution proposed was a poison bran mash. Davis gathered a group of farmers together one afternoon, mixed the mash and spread it on the field, anticipating the hungry grasshoppers would eat it the next morning. Many farmers returned the next day, but, to Davis' horror, there were very few dead grasshoppers.

"If you can't show us how to kill the grasshoppers, you can do nothing for us."

An entomologist from the USDA office read a newspaper account of the failed experiment and offered his advice: make sure the aroma is strong enough to attract the grasshoppers. Davis called the farmers together again, mixed the mash at 3:30 AM, and applied it to the fields just as the sun was coming up. Twenty-four hours later it was hard to find a live grasshopper or, one suspects, a still-skeptical farmer.

Melon Magic

In 1951, the university won a gold medal in the All-American trials for its hybrid watermelon, the "New Hampshire Midget." This melon subsequently became popular with consumers because it was a size that could fit easily in refrigerators.

The plant-breeding team of the late Dr. A. F. Yeager '52 and the late E. M. Meader '37, '78H continued to make improvements to the melon (the original Midget had a brittle rind that sometimes would break during transit or storage). They also increased the length of time the melon would remain deliciously edible. Seeds for their new introduction, the "Market Midget," became available for sale in 1960.

Microchips Ahoy

When UNH produced its first microchips, they were two millimeters square and had the work capacity of 3,000 transistors. (Modern microchips contain billions of transistors.) The chips were designed using the university's mainframe computer with the aid of advanced design tools from the Massachusetts Microelectronics Center.

Production of prototype chips had previously been done exclusively by industry at a cost of millions of dollars each. The center made the design of chips possible at a relatively low cost.

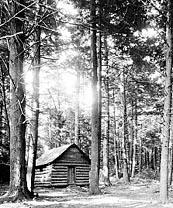

Spruce Hole

Southwest of Durham, near the Lee boundary, lies a unique geological formation called a kettle bog. Created at the end of the last ice age by immense chunks of melting glaciers, this area, known as Spruce Hole, is the last of six similar sites in New Hampshire.

In 1996, a team of researchers led by civil engineering professor Tom Ballestero used sophisticated equipment, including mini-piezometers, to determine hydraulic conductivity values at the site.

Back in the winter of 1918, two UNH students, armed with 200 feet of line, a five-pound weight, shovels, axes, measures and notebooks, set out to conduct their own research at Spruce Hole, exploring the age-old legend that the depth of the bog was unfathomable.

The New Hampshire reported on their findings:

By careful measurements the center of the surface was found and a hole chopped through twenty-five inches of ice. The line and weight were made ready and when all was clear the iron was started on its descent into the traditional bottomless pit. The line played out rapidly. Foot after foot was reeled off. Still the line disappeared into the depths below. Then the pull on the cord ceased abruptly. The watchers glanced hurriedly at the remaining line, and after vain attempts to sink it farther, pulled it in and measured off the distance. The pool is twenty feet deep at the middle.

Chemical Bonds

On April 16, 2004, the American Chemical Society presented Prof. Allen J. Bard of the University of Texas with the W. H. Nichols Award.

The award was established in 1902 by Dr. William H. Nichols, a pioneer in the US chemical industry and an early champion of the importance of chemistry in the future growth of the nation. A charter member of the American Chemical Society, he maintained a deep commitment to research and development and to the importance of supporting science education and students of chemistry.

The University of New Hampshire is pleased to be able to count two Nichols Medal winners among its faculty. In 1904, Prof. Charles L. Parsons, received the second medal ever awarded for his research and subsequent revision of the atomic weight of beryllium. In 1912, UNH was honored again, when Prof. Charles James was awarded the medal for his work in rare earth compounds.

Mr. Watson—Come Here—I Want to See Ewe

It is not generally known that the inventor of the telephone, Alexander G. Bell, was also interested in scientific sheep breeding. In 1885, he bought a summer home on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. Bell became fascinated by the sheep that lived there.

Observing that those with more than two nipples produced more twins, he decided this could be an important means of increasing wool and food production. Thus he launched enthusiastically into a study of the breeding of multi-nippled and twin-bearing sheep that continued for the rest of his life. He died in 1922.

Meanwhile, down in Durham, the Agricultural Experiment Station was also conducting experiments in applied genetics in sheep. Different breeds were crossbred, then selected over several generations for rapid growth, market conformation, and wool quality.

A bulletin, written by Prof. E.G. Ritzman about the experiments being conducted at the university, attracted the attention of the Bell heirs, and arrangements were made to transfer Dr. Bell's sheep to Durham. By adding the qualities of the Bell sheep, they eventually developed a strain with good growth and conformation, a high incidence of ewes with a high incidence of twinning, and wool of excellent quality.

Salute to Sousa

When we think of university research, the Department of Music may not be the first one to come to mind. However, research was the impetus behind the "Salute to Sousa" clinic held at UNH on January 13, 1951.

John Philip Sousa wrote his marches "on the fly," taking no time to record dynamics, accents and special effects, and published Sousa manuscripts were actually incomplete. Copyrights on his music were running out and abridged editions had already been published, thereby moving the music world further and further away from the real Sousa. Only those musicians who had performed under the baton of the "March King" himself possessed the knowledge of authentic Sousa tradition.

In a first-of-its-kind clinic, university band conductor George E. Reynolds arranged for three former Sousa band members to head all-day sessions to demonstrate the showmanship patterns and techniques of the late band master. Sousa music publishers provided condensed scores so that the clinic members could write in the additions and effects.

Band masters and music lovers from all over the East were invited to attend. Sousa's two daughters, Priscilla Sousa and Mrs. Helen Sousa Albert, were guests of honor. The day culminated in a concert by the 88-piece UNH band conducted by Dr. Frank Simon, former assistant conductor of the Sousa band. The band clinic received national recognition and the following year Sousa clinics were held in the Midwest and the far West.

Chemistry Lab, Quantitative Class, 1922

Sciences of the Home

From the 1913 college bulletin introducing the new four-year course in Home Economics:

The College has been for many years coeducational, and has offered its facilities alike to men and women. The new course is arranged to provide for young women special and technical training in subjects of greatest value and interest to them the same way in which other subjects of particular interest to young men are provided. It is a recognition of the fact that the sciences and economics of the home are as important as those of the shop or farm.

Truly Evergreen

Although the Office of Sustainability was not established at UNH until around 1997, the idea of sustaining the environment is not a new one on campus.

In the December 10, 1919 issue of The New Hampshire, Prof. K. W. Woodward of the Forestry Department suggested that instead of cutting down a tree for Christmas, it would be better to set one out.

"It usually happens," he says, "that the straightest and most likely trees are selected for Christmas and are afterwards thrown away. Not only are the woodlands deprived of these trees year after year, but the tree's usefulness is only a transitory one."

He suggested a permanent community Christmas tree set out near the church or town hall. For family Christmas trees, Prof. Woodward suggested, "a conifer from three to four feet high be dug or purchased and afterward set out on the lawn."

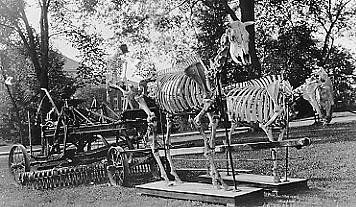

Tractor School

In the spring of 1920, New Hampshire College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts (as UNH was then known) offered farmers and gardeners of the state the opportunity to learn how to operate tractors at the first Tractor School ever held in New England.

Tractors were first mass-produced starting in 1916, and Prof. Taylor of the agricultural department estimated that their use in New Hampshire was increasing at the rate of fifty new tractors a year.

For three days, students listened to morning lectures on such topics as "Motor Farming" and the "Principles of Tractor Design." The afternoons were devoted to practical field instruction in tractor operations. Demonstrated by company representatives were five large tractors—two Fordsons, a Cleveland, an International, and a Moline—and two small garden tractors or motor cultivators, a New Britain and a Utilitor.

Eighty-one people, both men and women, took advantage of the Tractor School for a registration fee of $1 plus $2 a day in room and board.

Student Teaching

Mrs. Lucinda Smith was a popular English teacher at UNH from 1920 to 1957. When asked to talk about some of her experiences during her long career, she remarked, "Teaching students sometimes educates the teacher." She continued:

One evil day, I slipped a theme of my own in with the typed unsigned themes of my students… I wriggled and squirmed as my work was thoughtfully read, critically evaluated and finally pronounced ‘fair with a tendency to sentimentality.’ And they were right.

The Last Supper, 1939

One of the more astonishing photos in the university's historic photo collection is this one, titled: "Depiction of Last Supper at UNH," 1939.

A little sleuthing through the archives and the mystery is solved. For many years the university hosted the Northern New England School of Religious Education. Young people and adults came from eight states for the week-long program of Christian leadership training, which included "a complete curricula of lectures and discussion courses in the morning and a well rounded recreational program of games, drama and stunts in the afternoon."

Mister Kara's Neighborhood

In 1952, the Federal Communications Commission set aside 242 television channels for the use of non-commercial educational and cultural interests. After almost a year, only one station was on the air and 11 construction permits had been granted. The future of educational television looked bleak, unless you were one of the 200,000 weekly viewers of UNH physics professor John Karas' show, "Science Sketches," airing on Boston's WBZ-TV.

Ignoring his critics, Karas felt that to hold an audience, educational television needed to be entertaining. He gave each show an intriguing title and used simple terms and household items in his demonstrations so they could be repeated at home. He often invited guest scientists to keep the show interesting and varied.

His most successful teaching aid was a robot named "Tobor." Although touted as a mechanical genius, Tobor sometimes made mistakes and often found it hard to understand everything, which allowed Prof. Karas to make his explanations simple enough for all to understand. Although his show was aimed at children, fan letters indicated that the show was popular with adults as well.

Live! From Durham

When Channel 11 was established at UNH, it was expected that the TV station would be used in the instructional program of the university, but only two attempts were made to do so.

Under Prof. George Moore, lectures for the basic freshman course in biology were broadcast starting in 1960–61, with students gathered in a large lecture hall that had been equipped with TV receivers. Prof. David Long gave his course in US history over open-circuit TV. Long's lectures appealed to the off-campus audience and were picked up by stations in Boston and Albany.

University students, however, did not like the television classes, preferring live, if less colorful, teachers. Both experiments were soon abandoned.

Creative Writing

Carroll S. Towle taught creative writing at UNH from 1931 until his death in 1962. His students frequently won national recognition in the Atlantic Monthly contest for college students.

Towle once described his approach to teaching as "inductive," distinguishing it from the deductive methods of his colleagues. From Dan Ford '54, a former student of Towle, who is now a successful writer:

Whatever it meant in theory, inductive teaching was chaotic in practice. Take, for example, the Case of the Sixth Point. Towle came into class one morning and announced that we would consider the Sixth Point that day. There had never been any consideration of the first five points, at least not to our knowledge, but we dutifully recorded the numeral in our notebooks. For the next 50 minutes Towle lectured us upon some esoteric technique of the writer's art—point of view, perhaps. And just before he dismissed us he said, 'Unfortunately, we didn't manage to reach the Sixth Point today, but we will take it up next time.' We never heard of it again.

Memorable Mentors

In a poll of "best-remembered" teachers, conducted in connection with the Golden Jubilee fund drive in 1972–73, a total of 365 teachers were named by the 2,044 alumni who voted.

William Yale, history, took top honors, ranking first with classes graduating from 1930–49. Other firsts were Ernest R. Groves, sociology, before 1919; Donald C. Babcock, history and philosophy, and Leon W. Hitchcock, electrical engineering, tied in 1920–29; G. Harris Daggett, English, 1950–59; David F. Long, history, 1960–69. William G. Hennessy, English, impressing students over three decades, tied for second in 1940–49 and received honorable mentions in 1920–29 and 1930–39.

At a disadvantage in the polling, because of their more limited exposure to students, teachers in the agricultural and technical departments who ranked high included Frederick W. Taylor, agriculture, before 1919; Charles James, chemistry, before 1919 and 1920–29; Harold A. Iddles, chemistry, 1930–39 and 1940–49; and Edmond W. Bowler, civil engineering, 1930–39.

Life Studies, Rest in Peace

One of the most innovative additions to the university's offerings was the Life Studies Program, initiated in 1970. This experimental program was designed as an alternative path to "general education" in the first two years of the student's college career.

Instead of traditional classes, there were workshops designed around multi-disciplinary themes such as Perception and the Creative Arts, Spirituality, and Environmental Issues. The students were expected to share actively in the decision-making process regarding the structure of the course. No tests were given and the only grades were credit/fail. The student was counseled in their course selections to prepare them to enter their major's curriculum by their junior year.

Seventy-five freshmen enrolled in the program, but few were willing to assume the active leadership roles that the program required to function. Life Studies was dropped after only two years.

Cats' Cradle

When the historic submarine USS Albacore was being docked in its final resting place in Portsmouth, NH in 1986, it hit the steel structure on which it was to be placed for display. As a result, the Albacore had to be floated into position and supported aft by temporary cradle blocks.

Eugene Allmendinger '50G, '92H, professor emeritus of naval architecture and vice president of the Portsmouth Submarine Memorial Association, put out a call for volunteers to submit designs for a new cradle to replace those rejected by the Navy.

Mechanical engineering technology students Randy Colby, Ray Hebert '87, and Matt Parker '87 answered the call. Their successful design was done as part of a design course taught by Prof. Ralph Draper.

Tilting Windmill

In the fall of 1978, 45 students in the civil technology program at the Thompson School of Applied Science enrolled in the Energy Management program, the first of its kind in the Northeast. The program prepared students to become certified technicians who could analyze the interrelated possibilities for making buildings more energy efficient.

The program came to the attention of Boston's best-known meteorologist, Don Kent. In the summer of 1984, he donated a wind turbine and an electric generator for use in the Alternative Energy Systems course.

The wind turbine stood about 90 feet high with a 24-foot-diameter propeller. The 5-kilowatt generator was connected to the UNH power grid, with the expectation that it would save the university about $200 a month. Thomas March, mountain climber and associate professor of agricultural mechanics, and Arthur Leclair, instructor of applied plant science and tree climber, were recruited to help install the turbine near Putnam Pavilion.

Five years later on a bitter cold winter day, March's talents were again called upon when an eight-foot section from one of the blades broke loose and crashed through the roof of greenhouse No. 5. The only way to completely stop the off-kilter windmill was to climb up and manually disengage the mechanisms. The wind turbine and generator were deemed beyond repair and both were scrapped.

Athletics

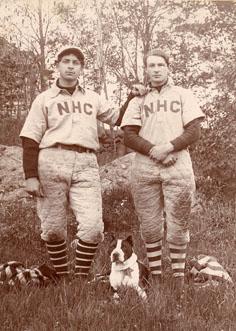

Baseball players Fred F. Hayes & Fred W. Smith, 1897 team

Either Better Batters or Worse Pitchers

The 1897, the New Hampshire College team experienced one of the most unusual baseball seasons in history. The nine played seven games but only one score reads like modern tallies: Exeter Athletic Association 16, New Hampshire 2.

In the other six games, of which the college team won only one, New Hampshire amassed 241 runs to their opponents' 279. The highest scoring game was against Colby College, in which the Maine Mules squeezed out victory, 60 to 55. Other high scoring games included: Andover 34, NH 37; Bates 49, NH 40; Bowdoin 49, NH 33; Brewster Academy 49, NH 42.

Secret Stash

It was "Old Home Week" in 1935 when many of the university's best athletes returned to campus for the New Hampshire Banquet. During the inevitable round of stories, baseball coach Hank Swasey told this one about Ralph Brackett '18, who was then coaching baseball at Portsmouth High School.

Swasey noticed that the ball had rolled far into the underbrush, so when the teams changed sides, he hurried to the spot where Brackett had picked up the ball. Bushing aside some leaves, he discovered a half dozen baseballs hidden but still within reach.

Ralph played right field when he was not catching, and the home field had a short right field, with a thick underbrush, where baseballs had habit of disappearing with amazing frequency.

After a time, Brackett began to reappear more and more rapidly with the balls, and soon long drives were being held to singles.

On a day off, Swasey decided to investigate. He parked himself along the right foul line, and sure enough, a batter drove a long hit into the bushes. Brackett chased it, reappeared suddenly, and threw the runner out at second. Swasey noticed that the ball had rolled far into the underbrush, so when the teams changed sides, he hurried to the spot where Brackett had picked up the ball. Bushing aside some leaves, he discovered a half dozen baseballs hidden but still within reach.

Whatever You Say, Coach

Andy Mooradian '48 coached the UNH freshman baseball team for thirteen years. The game he remembers best is not one of the many he won: The UNH frosh led Exeter Academy 2–1 in the ninth. Exeter had two outs and two strikes on a batter who swung and missed a pitch in the dirt.

As the UNH catcher dug the ball up, the batter, still not out, broke for first. The frosh catcher, excitedly celebrating the apparent victory, did not notice. "Throw the ball, throw the ball," Mooradian shouted from the dugout. The catcher promptly threw the ball to Mooradian! Awarded second base on the overthrow, the Exeter boy scored on a blooper just over the infield to tie the game at 2–2.

Home Free

Earl E. Lorden, a distinguished coach of the University of Massachusetts baseball team tells this story.

UNH loaded the bases against their Bay State rivals and a Wildcat pounded a pitch over the right fielder's head. The ball rolled to the fence with the fielder in blazing pursuit. In fact, the UMass player was running so fast that he put his foot up to keep himself from crashing into the fence. His spikes got stuck in the fence. He could not free his foot and, with the ball just out of his reach, the UNH runners gleefully circled the bases.

Green Monster Memories

On a beautiful May afternoon in 1990, 400 fans accompanied the UNH baseball team to its game against Boston University. The team was on a seven-game winning streak, but better than that—with the Red Sox away on a West Coast road trip—the team was playing in Fenway Park!

"It's a dream come true for many of the kids," said coach Ted Conner before the game, gazing over the Green Monster toward the Citgo sign in Kenmore Square. Players, toeing the dirt in front of the third-base dugout, grinned at each other and spoke in hushed tones. All of the Wildcat players entered the game and had their chance to play. Keeping score was almost beside the point, but the Wildcats beat the Terriers, 13–4.

On to Victory

The November 1902 issue of the New Hampshire College Monthly was full of optimism for the football team that season:

We congratulate Dr. Scannel on the good results he is getting. The victory over Boston College was well earned. He is infusing the right kind of spirit into our men... The development of the college yells under the leadership of Professor Whoriskey and Adams, '05, has been very marked. One would hardly recognize the old 'Rick-a-chic-a-boom.' The cheering has proven a great help to the players and cannot but help them to victory.

Most Valuable Player

In the early years at UNH, it was a challenge to find enough men to play football and have a second team to scrimmage with. It was not unusual for faculty and staff to volunteer for the scrimmage team. One such man was physics professor Artie Nesbit.

Student Wilfred Osgood, Class of 1914, recalled seeing Nesbit, night after night, playing in the line against the students. "It was due to this spirit and encouragement that the early teams turned out as well as they did," he said. "A uniform at that time consisted chiefly of a jersey, a pair of pants, and shoes, and there were hardly enough of these to equip two teams. Any accidents to a uniform meant a repair on the field, at once!"

Football Fanatics

The November 1904 issue of the New Hampshire College Monthly has this account of a memorable celebration following a football victory over Tufts College:

The news that New Hampshire had won by a score of 4–0 was received about 7 o'clock in the evening Sept. 28, and almost immediately the celebration began. The student body formed in line armed with revolvers, guns, and other noise-making instruments, awaiting the arrival of the team, but it was soon found out that the team would not return until morning.

This, however, did not put a stop to the demonstration, for the line then proceeded to the houses of the different professors, announcing the news to them... The college bell rang out loud throughout the time of the demonstration. The following morning the student body was on hand at the depot and scarcely had the 8:17 pulled into the station and the member of the team stepped out, when each one was seized, cheered, and carried to his room on the shoulders of his fellow-students…

In spite of the rain, which poured during the afternoon and the first part of the evening, a large quantity of wood had been collected and everything was ready for a good bonfire at 8 o'clock. Everybody rallied around the fire, and the noise coming from that spot could be heard in the farthest corners of the town. After the bonfire a nightshirt parade was held and the celebration ended.

Sore Loser

Back in the mid-twenties, UNH coach Bill Cowell and Tufts coach Arthur Sampson were bitter rivals on the field but boon companions after the game was over. In '26 the Wildcats defeated Tufts 28–3 and Cowell invited his friend to have dinner with him the following year after the game. He even agreed to shoot some ducks and prepare them at his house.

The game in '27 was all Jumbo; Tufts beat New Hampshire 39–0. Sampson looked up his old pal after the game, saying, "now where are those delicious birds?" To which an irate Cowell replied, "Go shoot your own ducks. And what's more, clean 'em and cook 'em." A 39–0 score stretches even the best of friendships.

A Shot in the Dark

In 1939, George Sauer and his Wildcats played an interesting night football game at Springfield College. The host had rented portable lights of dubious voltage, and after four periods of staggering around in the darkness, Springfield won the game 3–2; a field goal against a safety.

A sports writer covering the game sent in a flash lead with just the score. Before he could start to file his story his editor wired back, "Who pitched?"

Roll 'Em!

In the 1940's, head football coach George Sauer considered going to the movies as perhaps a player's most valuable asset in perfecting his game. A salvaged wind-mill, stripped of its machinery and dressed with a covered platform, allowed UNH photographers to film the action on the fields below. The films were then shown in slow-motion to the team so players could see mistakes and good plays.

Glass Bowl Remembered

After 49 years as a major sport at UNH, football finally produced a winning team worthy of an invitation to the Glass Bowl at the University of Toledo on December 6, 1947.

The newspapers were all abuzz. A year before, in 1946, the football program had just resumed after a three-year wartime hiatus. Under the coaching of J. William "Biff" Glassford, the team ended its second season with a 6–1–1 record and won the Yankee Conference.

The following season, the team came out strong, winning games by resounding scores: 55 to 6 over Northeastern and 34 to 0 over Tufts. After six straight wins, the undefeated team found themselves looking towards the last two games against Boston University, and then their biggest rival, the University of Connecticut. They beat BU 13 to 7 in a rough, tough game. The game against UConn was another slam-bang affair, but they came from behind to win it 14–7.

The Glass Bowl matched the top Yankee Conference team with the Mid-American Conference champions, which that year was the University of Toledo. UNH was the underdog both because the Mid-American was the stronger conference and the Glass Bowl was Toledo's home stadium. The Wildcats fell behind early and lost by a score of 20–14, despite a record-breaking 84-yard touchdown reception by Bob Miksen '50.

It would be twenty-eight more years before UNH would again be invited to play a Bowl Game.

Putting Their Heads Together

During the Glass Bowl era, Coach J. William "Biff" Glassford had two talented quarterbacks, Bruce Mather and Bill Levandowski. Mather was acknowledged as one of the all-time greats in New England collegiate football, hence Bill spent most games on the bench.

Once late in the season, with the Wildcats on the ten-yard line moving into score, Glassford motioned Bill into the game. But not without certain instructions. As the team huddled Bill growled, "Now shut up you guys, the Coach says I'm the boss. I'm running this team, understand?" There was dead silence for about a minute, until Bill timidly mumbled, "Anybody got any suggestions?"

Rocket Buster

The Glass Bowl expedition, aside from its football aspects, was also a goodwill expedition to the Ohio hinterlands. Representatives for the State Planning and Development Commission seized the opportunity to advance the merits of New Hampshire poultry, among other things. They took with them on the team train a rooster of the New Hampshire breed and staged a contest for the best name.

The winning name, "Rocket Buster" was submitted by Al Juris '50, a lineman, who was awarded the five dollar prize money. "Rocket Buster" was photographed as often as the football team and graced the pages of the Toledo Blade before the game. During halftime, it was presented to the governor of Ohio.

Winner's Circle

The highlights of the 1958–59 freshman hockey season were a 7–1 win and a 2–2 tie, both against New Hampton. Their seven other games were losses.

That spring, when Coach Snively submitted his recommendations for class numerals to the Athletics Committee, there were 16 names on the list and this note:

Only six players have met requirements; however, the others have earned them through their loyalty, service to the above six in scrimmage, perseverance and determination and regular attendance. They did not have much playing time, but we could not have played our games without them.

The committee approved the awards.

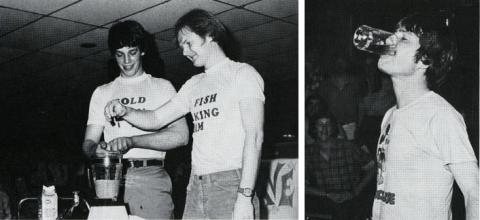

Big Fish Story

Ever since UNH fans started throwing a fish on the ice after the first goal at UNH men's ice hockey games, some pretty good fish stories have evolved. In an article in the Winter 2001 UNH Magazine, UNH head coach Dick Umile '72 told the tale of the time the UNH mascot, Wild E. Cat, attempted to throw the fish in Snively Arena.

When Wild E. Cat threw the fish, it hit a Yale assistant coach. (The costume—as those who have worn it will attest—obscures all but a small line of sight.) "The assistant coach was an Italian guy, and they called him the 'Godfather'," says Umile. "They now call him the 'Codfather'. The guy came up to me after the game, and I apologized. What could I say? It slipped."

Crowd Control

Bill "Butch" Cowell was hired in 1915 as the first full-time coach. He ran the athletic department until 1939. The respect he commanded is illustrated by this story.

At a Mass. State basketball game in 1935, the crowd began to loudly express their displeasure at the number of fouls being called by the referees. Suddenly, the booing ceased, and the crowd became tense. For Athletic Director Cowell was striding forth on the floor. He gruffly called the referees into conference.

The crowd waited expectantly, almost hoping that the Butch would side in. But old Bill Cowell was perturbed, and it wasn't at the referees. In very plain language he told the referees that if they wished to call a foul on the crowd for booing, to do so, and also to call any foul they saw for the remainder of the game. Butch retired and the crowd subsided, content to leave the matter in his hands.

Match Point

The UNH Faculty Tennis Association was formed in 1914 when Dean Charles Pettee and two other faculty members each gave $100 to build their own tennis courts. For nineteen years, the members of the Association were exclusively male faculty who, at certain times of the day, were allowed to entertain "female guests."

Mayme MacDonald (second from left in photo), who joined the faculty in 1923 as head of the department of Physical Education for Women, was one of the association's most notable guests. MacDonald received her undergraduate degree in science from the University of Washington and a Master's degree in education from Columbia University.

Her serving wasn't much, but her placement drives were wonderful… Had a few more sets been played, it is probable that Dr. Howes would have been defeated.

In college, she played field hockey, basketball, baseball, and rowed crew, but it was in tennis that she excelled. When she arrived at UNH, she ranked with the first six women tennis players in the country and held the National Clay Court, Bermuda, and Ohio State Championships.

Physics professor Howard Howes, one of the more avid tennis players, was only too happy to pair up with MacDonald for a game of mixed doubles. Together they handily beat their opponents.

On the day they played against each other in singles, they drew one of the largest crowds ever to turn out for any of the faculty contests. Although Howes ended up the victor, The New Hampshire reported this about MacDonald: "Her serving wasn't much, but her placement drives were wonderful...Had a few more sets been played, it is probable that Dr. Howes would have been defeated."

Olympics Bound

When the late Edward J. Blood '35 was a little boy, he strapped a pair of barrel staves to his shoes and started skiing. After his family moved to Hanover, NH he borrowed a pair of real skis and learned by trial and error and by imitating others more expert than himself.

When he entered UNH in 1930, he took up cross-country skiing and the newer types of skiing such as downhill and slalom. During his college years, Blood made an enviable record as an all-round athlete, winning 10 varsity letters. In 1932, he was selected by the Olympic Committee to represent the US in the third Winter Olympic Games held at Lake Placid, NY. He was the only undergraduate on the American ski team competing in the combined cross country and jumping events. Of the 33 men in the event, he finished 14th.

In 1935, he was again selected by the Olympic Committee to represent the US at the 1936 Winter Games, opened by Chancellor Hitler in Berlin, Germany. Although the American ski team did not win any medals, Blood viewed the Olympic experience as a valuable opportunity. "The Olympic Games certainly make for better international understanding among athletes and, to that extent, may be instrumental in forwarding the cause of world peace," he later said.

Field Goal

In 1967, the University recognized the need for a new women's softball/soccer field. A field was designed for the area behind Snively Arena, but the projected cost of bringing in the necessary fill was prohibitive. The field plan was shelved for 15 years, until construction of the undergraduate apartment complex created an unforeseen but fortunate benefit.

Excavation for the new building created large amounts of dirt that would need to be trucked away, if no other use for it were found. By using this dirt as fill, the original projected cost of the field of $100,000 was cut to about $15,000. The Thompson School helped clear the area and did some of the surveying. The felled trees were used in its sawmill program.

Facilities Services Assistant Director John Sanders described the field as a university self-help project. "It really does your heart good, as corny as it sounds, to pull something like this together," he said.

Fighting Skiier

Ralph J. Townsend '49, '53G, who was born in Lebanon, NH, graduated from high school in 1940 and enrolled at UNH. Along with studying horticulture, he was a four-event skiing star and a cadet in the Army ROTC program. His college career was interrupted by service in World War II.

Townsend responded to the National Ski Patrol's call for experienced outdoors-men to join the war effort. The Army's 10th Mountain Division, dubbed the "ski troops" by the press, specialized in mountaineering and cold-weather survival as well as military tactics, fighting on skis and snow shoes. He was a squad leader in the third platoon of K Company, 8th Regiment. In March 1945, K Company led the attack on the steep hill of Cimon della Piella. During the attack, Technical Sergeant Townsend was seriously wounded, for which he received the Purple Heart. Doctors predicted he would not be able to ski competitively again.

Townsend returned to his studies—and skiing—at UNH. During his junior year, he won the national Nordic Combined Championship, after which he was a member of the 1948 U.S. Olympic Team before repeating his claim to the Nordic Combined Championship title in his senior year.

Townsend began his career at Williams College in 1950 as assistant professor of physical education. During his 22 years as a ski coach, his teams regularly placed among the best in the nation. Among numerous other national awards he received for his career as both competitor and coach, he was named to the UNH 100 Club Athletic Hall of Fame in 1982, and the UNH ROTC Hall of Fame in 1988. Ralph Townsend died in May 1988, at the age of 66.

Faculty & Friends

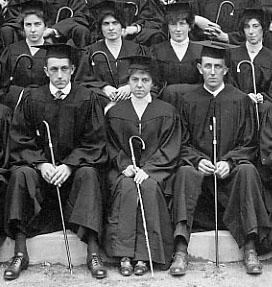

Leadership, Murkland-Style

The election of the Rev. Charles Murkland as the first president of the New Hampshire College of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts took many people by surprise. Those who considered the object of the college to train practical farmers had expected an agricultural authority of some prominence to be chosen to lead it.

Murkland was regarded with a great deal of suspicion, even by some of his new co-workers. Dean Pettee, however, supported the selection. In a letter to his wife dated May 24, 1894, he wrote approvingly of the new president's reaction to a bit of inter-class rivalry:

On my return [from Dover] I found the freshmen having their pictures taken in front of [Thompson Hall]. The sophomores had taken looking glasses and reflected the sun light from across the road into their faces. The freshmen went down and caught two of the sophs and tied them and had their pictures taken with the looking glasses behind them. They all kept good natured so no particular hurt was done. It was nearly over when the Pres came out. As no one was being abused or injured he did not interfere.

No Place Like Home

In 1914, Oren V. "Dad" Henderson moved to Durham from Topeka, Kansas at the invitation of the President Fairchild, who offered him a job in the Business Office. He arrived on a Sunday evening and spent the night at the president's house. Here is his account of his first view of Durham:

The next morning I left the house early to get a look at the surroundings of our new location, and started down the street to find the village. I passed, what I afterwards learned, was the home of Charles Wentworth, the A.T.O. house, the Pettee Block, Charles Schoonmaker's house and barber shop, a large three story building, Frank Morrisons' house with a livery stable to the rear, then a large house on the corner of Main St. and Madbury Road. At this corner, I met a man and asked the location of the Village and he replied, "you've come through 'er." I stood there, a stranger recently from a city of 60,000, with muddy feet, as there were no sidewalks, on a dirt street muddy from a rain the night before, and I said, "What a dump. About five years of this and back West for me."

Dad retired from UNH twenty-five years later.

Brooks Brothers Meet Montgomery Ward

An anecdote written down by Oren V. "Dad" Henderson, dating in the 1920s:

Dean Pettee was, for years, chairman of the Loan Committee. Students desiring a loan were asked to submit a financial statement showing required expenditures for such items as tuition, room and board, books, travel, clothes, etc. Being a frugal man, the Dean carefully scrutinized each expense in the presence of the applicant. On one occasion, a young man indicated he needed $75 for clothes. The Dean quizzed the young man concerning the necessity for such a large amount. On being informed that it was for a new suit, the Dean proceeded to lecture the student on such extravagance and to clinch his point he asked told him he had only paid $17.50 for the suit he was wearing. He then asked the men in the office adjoining his how much they paid for their suits. "$15 from Montgomery Ward," one answered. The other said he'd paid $16 for his. Whereupon the young man shook his head, saying, "I couldn't wear such clothes, Dean."

Pitching Professor

Whether you're a UNH alum, a member of "Red Sox Nation," or both, you may be surprised to learn that the first man ever to pitch a shutout for the Boston Red Sox served as president of UNH from 1927 until his death in 1936.

Edward M. Lewis was born in Machynlleth, Wales, on Christmas Day in 1872. When he was eight, Ted's family moved to Utica, NY, where he learned the American national game. He entered Marietta College in Ohio and then transferred to Williams College in western Massachusetts in his sophomore year. It was there that he became a star baseball pitcher. Ted graduated in 1896. To pay for his further education, he turned professional with the Boston Nationals from 1896 through 1900.

Lewis was unusual for his time, being a college-educated ballplayer who did not drink, who refused to play Sunday ball, and who read the Bible and said his prayers every day (hence his nickname "Parson"). At one time, he had considered becoming a minister, but decided he could have more influence as a teacher.

He earned his master's degree from Williams College in 1899. "The Pitching Professor" coached baseball at Harvard while he was still playing professionally, 1897–1901. In 1901, he jumped to the American League as a member of the first-ever Red Sox team. He won their final game of the 1901 season on a 5–0 shutout against Cleveland, the first in the history of the Boston Red Sox.

After the 1901 season, Lewis retired from baseball to devote his full energies to teaching. His lifetime record was 94–64, with an ERA of 3.53 and a batting average of .223.

Reading the Defense

William H. "Butch" Cowell arrived at New Hampshire College of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts in 1915 as the college's first full-time coach. Cowell was creative when it came to recruiting promising athletes. To make out-of-state students eligible for in-state tuition and scholarships, Cowell arranged for New Hampshire sports fans to "adopt" non-resident students, with court orders establishing guardianship.

In the 1920s, selective admissions policies and a restriction on enrollment resulted in some testy meetings of the admissions committee. Once, when Dean Pettee was ill and confined to bed, a member of the committee, Adrian Morse, who was more committed to raising standards than Pettee, took advantage of the situation by calling a meeting.

Pettee countered by asking for the meeting to be conducted in his bedroom. Morse realized he had been defeated when he saw Coach Cowell leaving the Pettee residence. The athletes whose applications were in question were not rejected.

Dear Student

In 1923, Registrar Oren V. "Dad" Henderson started a tradition of sending a summer letter to all the enrolled students telling them what had been happening in Durham during their absence. The 1926 letter includes these tidbits:

- "Coach Cowell spent about three weeks in Cape Breton Island. He returned Aug. 6 with a fine lot of fish which he generously distributed among friends. All fishermen will be pleased to hear the Coach's stories about how long it takes to land fish in that far off country.

- "As the street and roads in and about Durham are to become safe for driving, since the rule went into effect prohibiting a certain group from cluttering up the highways with cars of doubtful vintage, the following faculty people have purchased new cars: Profs. Richards, Case, McNutt, Woodward, Slobin, French, Wellman, Howes, Rudd, Swasey, Huggins and DePew. Taylor, Scudder and Ritzman have had theirs repainted while many others have had mud guards repaired.

- "That old and often discussed question, 'Resolved that there is more pleasure in pursuit than in possession,' will soon be decided by the following: Blake, Kalijarvi, Maitland, Gildow, Manton, Lloyd and Lowry. They will all be married before you see them again.

- "On July 17, I celebrated my 25th wedding anniversary by hiking to the top of Mt. Washington via Tuckerman's Ravine with my two youngsters, Helen and Hennie. Mrs. Henderson, not being a hiker, swatted flies in camp."

Doing What's Right

In his 1924 annual report, President Ralph Hetzel wrote: "No provision has been made... for retirement allowances to those who have given their life's work to the institution. The University has now reached the point where this question is acute."

The need for a retirement program was highlighted by the situation of Professor Charles Scott, who had started his career with the college in 1876. Following a stroke in 1918, having no other means of livelihood, he had returned to teaching in January 1919 even though he was nearly blind and deaf. He was able to read his lectures but was not aware of what was going on in the class.

History professor Donald Babcock went to Scott's class on the top floor of Hamilton Smith Hall one day, to discover that the boys had reached out the windows to get icicles off the eaves, which they were tossing about the room. Babcock entered by a side door and quietly chided the students for taking advantage of a man who could not defend himself. The class settled down, and Babcock left without Scott knowing he had been in the room.

In 1925, Scott was given an undemanding appointment as university historian, and relieved of his teaching duties. He died in August 1930. Fourteen years after Hetzel first broached the subject, the Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association program was put into effect at UNH.

The Milk Man

In 2006, 1,850 undergraduates and 574 graduate students earned degrees from 216 different programs. The following fall, nearly 600 more freshmen than expected sent in housing deposits. One hundred and thirty years previously, the New Hampshire College of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts (as UNH was then called) had the opposite problem.

In the fall of 1877, not a single student appeared to register as a member of the class of 1880. During the course of the year, two young men enrolled in the college, but both eventually dropped out. In the fall of 1878, Charles Harvey Hood of Derry qualified to enter the middle year, and thus became the only person to graduate as a member of the class of 1880.

After graduation, he joined his father's dairy business and was soon president of H.P. Hood & Sons Milk Co., one of the largest dairy product companies in New England. Charles Hood was an enthusiastic alum and a generous benefactor to the college. He was a member of the Alumni Council for six years during the formative days of the Alumni Association, and then served on the first board of directors.

In 1929, Hood was the unanimous vote for Alumni Trustee. Over the years, he also established a number of scholarships and achievement prizes. On the 50th anniversary of his graduation, he gave the school its first major gift from an alum: a modern infirmary with accommodations for 30 patients. Hood gave $125,000 for construction of the building and an additional $75,000 for its maintenance. Hood House was dedicated on June 12, 1932.

A Degree of Kindness

One Sunday in 1916, the president of Amherst College invited Prof. Edward Lewis, of the Massachusetts Agricultural College, to his home for a poetry reading. Well-known for his elocution, Lewis was asked to read the poems, including several written by one of the newest professors at Amherst, Robert Frost.

You don't know what ideas you were putting in my head… One dangerous one was that I ought to be ashamed to live anywhere but in New Hampshire. You watch the idea work. I predict that it will land me back in the state where my father was born and three fourths of my children and practically all of my poetry.

The two men discovered they had much in common and became lifelong friends. In 1927, Lewis became the president of UNH, and on June 16, 1930, he was delighted to confer an Honorary Doctor of Letters from UNH on the famous poet.

A week later, Lewis received a letter from Frost, who wrote:

The degree you gave me was different from any other I have ever had; the hood will be the one I wear if I ever have occasion to wear a hood. You made me realize that your friendship had in it an element of personal affection: it went beyond a mere admiration for what I have done. I deserve a little friendship of that warmth in a life mostly subject to cold criticism. At any rate it goes to my heart, and whether I deserve it or not, I am going to cling to it. We must see more of each other in the years to come than we have in the last few. I am coming for the visit in the fall and you must come for a visit here when you can. You were all so kind to us. It was family to family wasn't it. The honor was much, but the kindness was much more. Ever Yours, Robert

The sincerity and depth of their friendship is evident in the text of Lewis presentation, in which he chided Frost for leaving New Hampshire for Vermont. A few days later, Frost wrote to Lewis:

You don't know what ideas you were putting in my head... One dangerous one was that I ought to be ashamed to live anywhere but in New Hampshire. You watch the idea work. I predict that it will land me back in the state where my father was born and three fourths of my children and practically all of my poetry.

Time Zones

In 1937, two of the university's most respected men held very different views on the need for Daylight Saving time. Registrar Oren V. "Dad" Henderson, who was also the Speaker of the House of Representatives at the time, was the first to sign the Act establishing Eastern Daylight Time in New Hampshire.

Holding the opposing point of view was Dean Charles Pettee. Pettee's granddaughter remembers "There were two mantle clocks over the fireplace in the Pettee's home. My grandfather would have nothing to do with Daylight Saving Time. As a result, one clock was on "Pa's" time and one clock was on "Ma's" time, so we were constantly consulting both."

Test Flight

In July of 1953, the university's first "jet-age" president took his first ride in a jet plane and declared that if he were 20 years younger, "I think I'd like to do this for a living." President Robert F. Chandler Jr. rode in an F-94C from Otis Air Force Base at Falmouth, Mass., during a routine inspection of the ROTC summer encampment of 35 UNH students.

Major Chappy James, 260-pound air commander just back from Korea, said that the president "did everything we ask a pilot to do; he'd have been a natural flier."

Gremlins in the Basement

In the spring of 1967, the Outing Club found themselves in need of a large space on campus in which to build a number of kayaks. Just when they were beginning to think they were out of luck, Mrs. John McConnell, the president's wife, offered them the use of two rooms in the basement of their home.

Dick Roberts '67 (in photo) and at least seven other outing club members quickly began setting up shop with the infra-red heat lamps, exhaust fan, numerous vacuum cleaners, saber saws, paint brushes and rollers needed to build the 13-feet long boats. Each boat took two or three days to build and they planned to build a total of 12 or 13 kayaks before returning the president's house to its former condition.

President McConnell commented with a grin on the weird noises and smells emanating from his basement, but said he was happy a good use had finally been found for the space. And according to Roberts, "Mrs. McConnell sorta likes it. She enjoys the gremlins in the basement."

Resolute Leader

In 1971, when the selection of Thomas Bonner for president of UNH was announced, the Manchester Union Leader began a series of articles and editorials with the intent of persuading him to resign before he arrived. (His friend and former employer, Sen. George McGovern, was then campaigning for the Democratic nomination for president.) Undeterred, Bonner came to New Hampshire and began a statewide campaign to rally support for the university, with a goal of making UNH a truly public institution.

In the three years of his administration, he developed a School of Continuing Studies, making educational opportunities more available to adults, expanded the Merrimack Valley branch of the university, and increased support for Cooperative Extension programs. For two consecutive years, he was able to reduce the high in-state tuition rates while successfully lobbying for increased state appropriations.

Bonner also spoke out for equality on the campus. "If arguments against the complete equality of women are weak and contrived elsewhere, they surely are completely without merit in a University community," he said in 1972.

Bonner, who died September 2 in Scottsdale, Arizona, went on to become president of Wayne State from 1978 to 1982. A leading medical historian, he wrote seven books on American medicine.

Counted Out

When Joan Leitzel was inaugurated UNH president, the program read that she was to become the 18th president of the university. On November 22, 2002, when Ann Weaver Hart was inaugurated, the program described her as UNH's 18th president as well. It wasn't a typo. How can this be?

The mystery has its roots back in 1866, when the college was founded in Hanover, NH. To save money, the New Hampshire College of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts was situated next to Dartmouth College so the two schools could share facilities and faculty. Each college, however, was to maintain its own identity and had its own governing body.

Between 1866 and 1892, three men served as president of the college's board of trustees: Asa Smith (who was also president of Dartmouth), George Nesmith, and Lyman Stevens. No one seemed to keep a count of presidents until the college, by then UNH, was getting ready for its 75th anniversary.

Since 75 years included the Hanover years, it seemed logical to include the Hanover presidents, even though they were actually board presidents not college presidents. By the time Everett Sackett's history of UNH was published in the mid-'70s, however, two of the early presidents had been dropped, leaving only Asa Smith. This new count continued until President Leitzel, overseeing a redesign of the university seal, discovered the error.

A mathematician by training, Leitzel ordered the mistake rectified. Thus, UNH's 18th president, President Leitzel, was quite correctly succeeded by UNH's 18th president, Ann Weaver Hart.

Alumni band warms up before the reunion parade, June 1962

Early Supporter

Albert Demeritt, a native of Durham, was born in 1851. The owner of a 300-acre farm, he was active in civic affairs, serving on many town and state boards, and was a member of the Constitutional Convention.

Demeritt was also an advocate of education and the fledgling New Hampshire State College. He drafted the free text-book bill, which became law in 1887 and was a model for other states.

In 1913, he helped pass an $80,000 appropriation for a new engineering building for the college, but he did not live to see its completion. While hunting woodchucks one morning, he climbed a fence and was killed when his gun accidentally discharged.

In his honor, the new building, dedicated in December 1914, was named Demeritt Hall.

Her Own Woman

Jessie Doe (1887-1943), an outspoken New Hampshire native and advocate for women's rights, served the university as a trustee from 1934-43.

The late Phil Wilcox remembered Miss Doe as a great supporter of home industries and arts and crafts.

She would wear the strangest collections of ornaments possible. One time she arrived at T-Hall for a meeting wearing a home woven skirt, head band, and a varied assortments of jewelry. On her breast she wore a very large carved wooden leaf (and it was remarked that she was wearing it a bit high up!) She also wore some sort of 'creeper' boots that were being experimented with by the Experiment Station.

Jessie Doe Hall was named in her memory.

Penny Wise

In 1960, the last living member of the class of 1900, Charles E. Stillings, gave $228,000 to the University Fund in memory of his father, whose diligence and self-denial made it possible for him to attend college. Stillings majored in electrical engineering, and joined the New Haven at the Cos Cob power plant in 1911. He worked as a foreman for 37 years.

He never earned more than $100 a week, but he proved to his alma mater that he knew what to do with it. He had this advice for his fellow alumni: "Whatever your income is, save some of it. Buy common stocks—blue chips are the best—and don't sell them. Be an investor, not a speculator."

Spacious

In an interview for the 1978 Granite, Rick Linnehan '80 was asked, "Is there anything that you wish you had known about when you arrived here as a freshman?"

He answered, "I wish I'd known I was going to be in a build-up. I was in one for half a semester, and if I had known then, no way would I have come here. I don't see why they don't put a higher priority on building a new dorm."

It's funny where hard work, study, a little stubbornness and a lot of luck will take you.

As uncomfortable as living in the build-up might have seemed at the time, perhaps it served him well 16 years later, when he shared the close quarters of the Space Shuttle with six other crew members.

Working on his bachelor's degree in animal science at UNH, Linnehan dreamed of becoming an astronaut, without really expecting that dream to come true. "It's funny where hard work, study, a little stubbornness and a lot of luck will take you," he has said.

His dreams and hard work took him first to the Ohio State University's College of Veterinary Medicine, then to the U.S. Army Veterinary Corps, and then on to NASA. He has now traveled on three space shuttle flights.

On his second mission in 1998, he served as the payload commander on the STS-90 Neurolab mission aboard the Space Shuttle Columbia. He took aboard a UNH flag, presented to him by then-President Joan Leitzel, who attended the launch.

Hallelujah

Since 1912, the University Folk Club has been promoting fellowship among women of the university community and helping women students. In December 1933, the president of the Club, Mrs. C. F. Jackson, submitted this announcement to The New Hampshire:

The University Folk Club were very surprised at their Christmas meeting by the announcement that their honorary president, Mrs. Lewis, together with President Lewis, had again given a generous contribution to the Women Student's Loan Fund of the above organization. This is the second year this gift has been made be Mrs. Lewis and her husband in place of spending the money for the Christmas greeting cards to the faculty as given in years past.

The Folk Club Loan Fund is not a large one, but at the same time has been able by its comparatively small loans, to help many a student girl in an embarrassing financial situation. For this reason, any contribution to this fund is reason for real rejoicing in the interests of our student girls attending the University.

Who Turned On the Light?

In 1944, then Governor Blood appointed Mary Senior Brown, a leader in New Hampshire Republican Party activities and a retired school teacher, to serve on the University Board of Trustees. Being one of only two women on the board, she was particularly concerned with any issues the women students might have. She made a point of arriving early to campus before the start of an all-day board session to visit the women's dormitories and to discuss their needs with the house mothers.

However, the house mothers' perceived needs for the students weren't always the same as those of the students themselves. In an interview with Brown in 1963, she recalled, "I don't believe the girls will ever forgive me for having a light installed outside of Congreve Hall. It was a lovely dark spots for dates!"

Forever in His Debt

In the summer of 1876, New Hampshire's fledgling state college was dealt a harsh blow with the untimely death of Professor Ezekiel Dimond.

Just seven years earlier, Dimond had been elected by the Board of Trustees to serve as the first professor of the College of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts, an institution that existed only on paper. Dimond was the perfect choice. A man of unlimited vision and determination, he not only taught all of the chemistry courses for the college, he also served as the business manager, recruiter, architect, supervisor of construction, farm manager, and lobbyist in the legislature.

On his death, the trustees stated, "Without Dimond's zeal, faith, and personal labor on behalf of an enterprise that absorbed all his time and thought, it is believed by many that the College would today be a vagary of the mind, rather than an accomplished fact."

Shortly after his death, however, the trustees realized the true scope of the school's indebtedness to the professor, when they found that, not only had Dimond neglected to pay himself all of his last year's salary, he even had advanced money to pay some of the college bills. The total amount owed to his estate was $4,075, a sum the college did not have available.

The trustees turned to John Conant, a wealthy philanthropist and friend of the college, for assistance. With his help, they were able to settle the debt to Dimond's estate. According to the 1877 financial report, these transactions left just 38 cents in the treasury for the new administration to work with.

Dry (Ice) Humor

Prof. Charles Scott was hired by the New Hampshire College of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts (as UNH was then called) as its first librarian in 1876. During the next 54 years he would also serve as a professor of English, history, and political science.

On the anniversary of his 51st year he was presented with a bound volume of letters of tribute to him written by former students, colleagues, and friends. The letters mention his unfailing courtesy, gentlemanly bearing, and dignity. Many also remark on his subtle sense of humor.

One example comes from Frederick Taylor, then Dean of the College of Agriculture. He wrote:

I recall very clearly, the first time I met you in the corridor of Thompson Hall about September 2, 1903. Being a newcomer I made some inquiry about the climate here and you replied with your characteristic drollery that 'most people enjoyed it very much in spite of the fact that the sleddin' got a leetle thin during July and August.

Fleur De Guerre

Dr. Ormond R. Butler served as head of the botany department from 1912 until his death in 1940. In 1919 his expertise was called upon to help settle a debate that was then raging in the New Hampshire legislature. The issue on the table was which flower was most deserving of the title of state flower. Rep. Charles B. Drake first introduced a bill to name the lilac New Hampshire's state flower on Jan. 9, 1919. Other legislators then filed bills and amendments promoting the apple blossom, purple aster, wood lily, Mayflower, goldenrod, wild pasture rose, evening primrose, and buttercup as the state flower.

A long and lively debate followed, regarding the relative merits of each flower. The apple blossom was a popular choice for many, but it was the prohibition era and some people regarded the apple blossom as a symbol of hard cider. Others took issue with the buttercup, since the color yellow was often equated with cowardice.

Finally, legislators agreed to abide by the decisions of two of the state's top botanists, Prof. Arthur Chivers of Dartmouth College and Prof. Butler of the New Hampshire College at Durham. Unfortunately, the two men found they could not agree on the same flower! Chivers favored the lilac while Butler championed the evening primrose. A vote was taken between the lilac and the primrose. The lilac won and was adopted as the state flower on March 28, 1919.

Outside Help

As a child, Evelyn Browne spent six months of the year going to school in Santa Barbara, California, and six months of the year in Canada with her family. Her father, Belmore Browne, was both a landscape artist and an explorer. For about half the year, the family led pack horses loaded down with tepees, cooking gear, an easel, and paints through the Canadian Rockies. When her father found a subject to paint, the family pitched camp.

In 1943, Browne joined the UNH faculty as an instructor in women's physical education. Because of the war and her own background, she believed that the time was right to teach survival skills and outdoor activities. The university, however, was not easily convinced. She established the university's riding program, coached riflery and basketball, and finally, in 1955, began teaching the first outdoor education courses.

Browne retired in 1981 and began her most ambitious project, the creation of an outdoor learning center on some of her property on Dame Road, now known as the Browne Center for Innovative Learning.

Conjugate "Flunk"

Hermon L. Slobin taught mathematics at UNH from 1919 until his retirement in 1948. Born in the Russian village of Smolian in 1883, he was 12 years old when he emigrated to America. Ten years later, he earned his B.A. from Clark University with highest honors. He continued at Clark to earn a Ph.D. in mathematics at the age of 25. His first teaching experience was at a night school, where the students were adults of foreign nationalities.

Devising his own teaching methods, he gave them any subject they demanded. In order to assure everyone's attention, he often had to keep his lectures going in four different languages: English, German, Yiddish, and Russian.

"I wasn't very big", he recalled, "and when one of those husky fellas started to get unruly, I used to back him to the head of the stairs so I could give him a push if necessary." Dr. Slobin was well known for his sense of humor. He told his classes, "Flunk is an intransitive verb. I don't flunk you, I merely record your flunk!"

Quint-Essential

The first UNH Faculty Club was formed in October 1910, "for social and intellectual purposes."

One of the events that fulfilled the social function was the annual Halloween party. Members bobbed for apples, held a balloon-inflating contest, danced, and dressed up for the competition for best men's and women's costumes.

Costumes ranged from the traditional witches and zombies, to farmhands, mad scientists, Dutch girls, and clowns. But occasionally they reflected current events, and in 1936 a group of nine got together to go as the Dionne quintuplets, their parents, a nurse, and the doctor.

It's Greek to Me

During her senior year, Doris Johnson O'Neill '38, recalled fondly that her favorite teacher, Prof. John Walsh, chairman of the Language department, was a huge baseball fan. "If there was an on-campus baseball game, Prof. Walsh would take his brief-case and we would all head for the field to watch the game. We were "in Greek class" as long as he had his briefcase with him on the bleachers."

Road Warrior

In 1907, Dean Fred "Pa" Taylor became the proud owner of the first four-cylinder car in Durham. It was only the third car in town, since A. W. Griffiths of Packers Falls owned a one-cylinder Oldsmobile, and college president William Gibbs owned a two-cylinder Ford. Taylor's car, also a Ford, had no headlights but was equipped with two oil lamps on the sides. For ignition, it used dry cells instead of a battery. The tires were 3 inches by 28 inches, cost $20 each, and were good for an average of 2,000 miles.

One day in the summer of 1908, the Taylor family climbed into the car, with Ma and Pa sitting in the car's seat and young Ralph ensconced in a box that Taylor had attached to the back of the car. On the first day of their journey to Crawford Notch, two consecutive blowouts forced a stop in Wolfeboro. While the Taylors and their car recuperated, the dean telephoned Dover for a new supply of tires.

On the second day, they ended up at the Flume House at Franconia Notch, where the car ran out of gas. Taylor walked the three miles to the nearest gas station, gas can in hand. On the third day, they reached their destination safely, with only a minor setback when they had to stop at the base of Mt. Washington to let the steaming engine cool down. The trip home was uneventful and was completed in one day.

In the five years Dean Taylor owned the car, he traveled 12,000 miles.

Mud Daubers

Pottery teachers Ed Scheier and Mary Scheier worked at UNH from 1940 to 1960. One of the activities Ed Scheier expected his classes to engage in was the digging of a new supply of clay from the clay pits behind the outdoor swimming pool. One student remembers:

Mr. Scheier gleefully provided us with an array of funny-looking accessories. At 103 lbs., 5'3", I was the smallest, so he had me wear a pair of yellow slicker trousers with suspenders that would have fit a man of 300 pounds, plus he had me carry a shovel with an eight-foot handle. The tallest person in the class, a lanky young man, was told to carry the smallest tool.

He outfitted the others with similarly silly-looking gear, pick and shovels, etc. Several were given five-gallon glass jars to carry, which we assumed were to be used to bring the clay we would dig back to the studio.

He marched this very peculiar-looking group single file across campus to the clay pits, attracting quite a few stares as we labored under our loads. When we finally got to the clay pits, he announced that we were not actually going to dig any clay! He had an abundant supply, but he wanted us to see what clay pits look like. The pick, shovels and slickers were just to attract attention, for the profile. And the glass jars? "To catch frogs!"

Record Breaking

Since 1928, hundreds of UNH undergrads have attended summer classes at the Shoals Marine Lab on Appledore Island at the Isles of Shoals. The original lab was the dream of zoology professor C. Floyd Jackson and his wife, who also taught science at UNH.

Floyd G. "Stubby" Bryant '31, '33G was the first student to register for the first lab. He also helped get the place ready, arriving with the Jacksons one late night. "It was ghostly; an eerie, barren-looking island with just one dim light shinning. And it was terribly quiet," he recalled.

An existing two-story Federalist house was converted into the lab's main building, and the students put an end to the quiet. Bryant remembers the professor gritting his teeth and hurling the record, "Muddy Water," into the bushes when students had taken to playing it nonstop on the Victrola.

New Hampshire's Bread Loaf

Carroll S. Towle taught English at UNH from 1931 until his death in 1962. Because of the success of undergraduate writing at the university and the growing prominence of several young graduates, Towle initiated the first Writers' Conference of the University of New Hampshire in 1938. Held each August on the Durham campus, it was one of the first popular university writers' conferences, and attracted a large number of distinguished authors each summer.

Eventually, it became one of the important centers of literary development in the East. In 1962, a review of summer writing conferences in Saturday Review rated the New Hampshire Writers' Conference as one of the Big Four of such conferences, and regretted its cancellation that summer. In fact, the conference was never reinstituted due to Dr. Towle's poor health. His collection of materials relating to the UNH Writers' Conference is housed in the University Archives.

Dog Days

William Yale, an authority on the Middle East, taught history at UNH from 1928 to 1957. For a number of years, Yale had a small dog that frequently accompanied him to class. The dog was well behaved, sitting quietly and attentively in the front of the room during the professor's lectures.

One day, however, as Yale lectured to his summer-school class on European and world history, the dog sat back, yawned quite audibly, got up, and left the room. This was too much for Professor Yale. Slamming his books together, he said, "If it's too dry for my little dog, it's too dry for you! Class is dismissed!"

Professor Dumbledore

Prof. Nobel K. Peterson taught in the Natural Resources Dept. from 1957 until his death in 1987. His course in Introductory Soils was very popular with students in part because of his extensive use of creative audiovisual effects.

In 1977, one of his classes presented him with a long black cape and the poem below.

As we watched you day after day it

Soon became obvious that you were

More than a teacher.

You bore the eccentricities of

Genius and Magic

But you were missing something

As you displayed your wizardry of

Media and soils

A wizard without a cloak?

A sad situation indeed

We could not bear to see it continue

So, from the Soils 501 Class of 1977

We add this cloak to your wardrobe

And the word wizard to your title.

Textile Mania

Irma Bowen came to UNH in 1920 to teach classes in the history of fashion and dressmaking techniques. During the course of her tenure, she collected many examples of clothing for use in her classes. By the late 1940s, the collection numbered over 600 items, including fashions from the 18th through the 20th centuries, children's clothing, and accessories.

After Miss Bowen's death in 1947, the Board of Trustees voted to name the collection The Irma Bowen Memorial Collection, as a tribute to her dedication as a teacher in the field of textiles. On September 20, the university hosted the fall symposium of the New England and Eastern Provinces of the Costume Society of America. The highlight of the day was the opportunity to visit the costume storage area of the University Museum.

Much to the surprise and delight of the participants, a blue-and-white striped homespun gown, circa 1800, was discovered. The gown is an example of "everyday" clothing from this period, which is extremely rare since most were discarded or used for rags once they were worn out. For more information on the dress and the costume collection, contact the University Archives.

Futurama

At a senior tea in 1944, Prof. Donald C. Babcock, head of the department of philosophy, gave a fanciful speech on an imaginary 25th reunion of the class of 1944. Among his visualizations for the future were roads consisting of two smooth lanes; one for pedestrians and one for wheeled traffic. People got around on motorized roller skates and there were landing pads for helicopters on campus.

Nation-wide television hook-ups lined the Field House walls, so alumni who could not attend the reunion in person could still be there. Course registration was done through the Central Scheduling System in Washington DC and lectures, transmitted electronically, were conducted only by the best men in the world.

Horse Power

In an article in the March 26, 1915 issue of The New Hampshire, Professor Otto L. Eckman of the department of animal husbandry urged New Hampshire farmers to continue to raise horses, saying:

The automobile is not only not going to put the horse out of business, but that there are today more horses in the United States than there were 15 years ago when the auto was first coming into use, and that the average value of the horse is greater than at that time. (#109)

Hitting the High Notes

In 1942, the music and art departments were quartered in Ballard Hall with the pottery studio in the basement. The pottery instructor, Ed Scheier, wanted some life object for his students to model, so he obtained a fine New Hampshire cockerel from the poultry department.

Working alone one afternoon, Scheier was surprised by the arrival of a girl, with fire in her eyes, demanding to know who had been imitating her in her vocal efforts. Just then the cock crowed, thereby answering her question.

Last Wish Honored

University librarian Thelma Bracket's 1952 annual report includes this note:

The library has treasured since [the death of former librarian Charlotte Thompson] a box of letters written to her by her "boys" in the first world war; letters from all over the world. Previously undiscovered in the box was a request in Miss Thompson's handwriting that the letters all be burned at her death. The librarian, of course, had no choice but to obey.

Dressed for the Occasion

Prof. Loring V. Tirrell taught animal husbandry at UNH from 1920 to 1966, and was head of the department from 1930 to 1963. Of the more than 4,000 students he taught, few left his classes without catching some of his contagious enthusiasm for the subject.

Tirrell initiated a program at the university dedicated to improving several of the horse breeds. It was not unusual to see his big black Cadillac, racing through Durham in the early hours of a spring morning, on his way to the stables where a mare was about to foal.